Arilès de Tizi on Turning Exile into Art

Arilès de Tizi

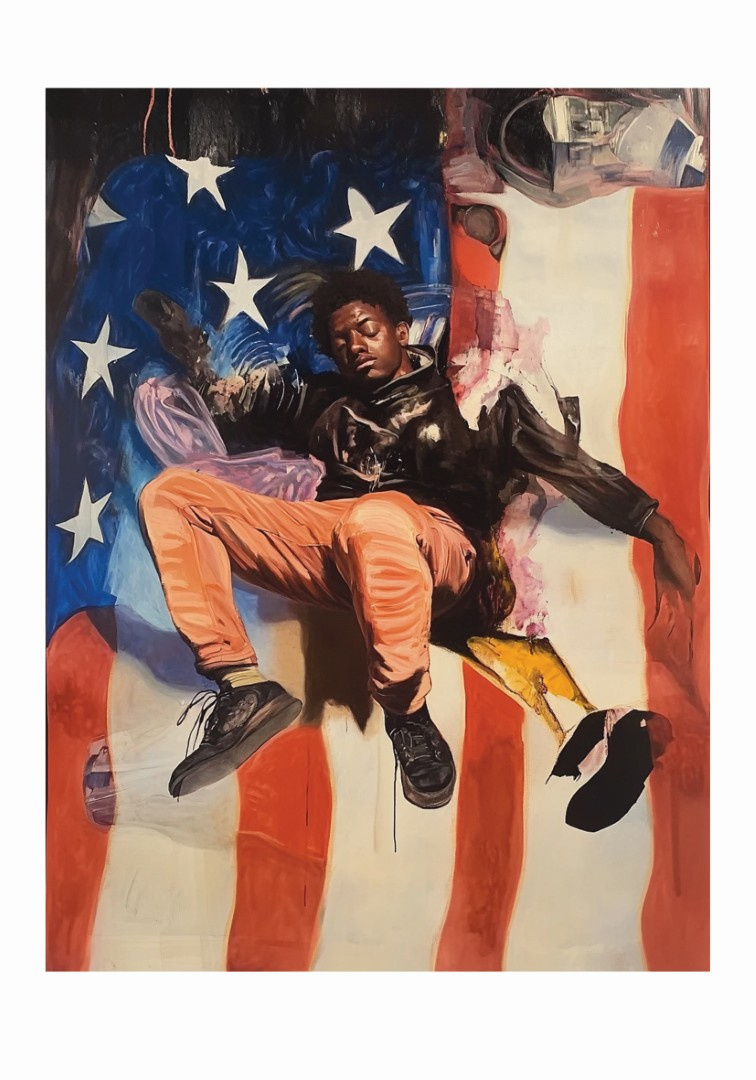

Born in Hussein Dey, Algiers in 1984, and raised in the working-class neighbourhoods of Paris, Arilès de Tizi is a Franco-Algerian artist whose work captures existential moments – both sacred and profane – in urban environments. Living between Paris, New York, and Tokyo, Arilès reimagines identity as fluid and collective, with his work fusing canonical cultural symbols with expressions of belonging in urban settings to question a stubbornly colonial attitude to culture, migration, history, diaspora, and more. His process moves fluidly between painting, photography, installation, and digital media, transforming stories of migration and exile into transcendental acts of resilience and (often) nobility as part of a revised cultural narrative.

FAULT: How did growing up between Algeria and France shape you as an artist?

Arilès de Tizi: I grew up between two truths that never really looked at each other. Algeria gave me a sense of origin, of silence, and of loss. France gave me the language of exile, and the awareness of fracture. Somewhere between the two, I learned how to turn absence into images. What I create now comes from that tension between memory and becoming, between holding on to what shaped me and the need to invent new ways of belonging. My work still carries the marks of that journey, that of a child of exile who became a witness to his own displacement.

You’ve said your work is “born out of exile.” How does that experience continue to shape what you create today?

Exile isn’t something that ends with a border crossing; it seeps into you and stays. It may start as geography but becomes something more intimate, a rhythm of being slightly out of place everywhere. You don’t outgrow it with a passport; you just learn to carry it differently. It’s the space between languages, between what you’ve lost and what you’ve managed to rebuild.I don’t paint to escape that space; I paint to inhabit it. My works aren’t nostalgic; they try to hold contradictions together, beauty and violence, pride and shame, belonging and solitude. Exile, if anything, sharpens the senses. You start noticing what others pass by too quickly to see.

What first drew you from graffiti and photography into painting and installation?

Graffiti was my first act of rebellion, a way to exist without permission. It taught me that visibility can be an act of defiance. Photography, on the other hand, taught me to look, to observe the light, the silence, to listen to what is not said. Painting taught me something different… time. Installation arrived later, almost naturally, as a way to create environments where people don’t just look at displacement but feel it in their bodies. Each medium feels like a border crossing. I move between them the way migrants move between worlds, not looking for comfort but for coherence.

How do you balance personal memory with political history in your art?

I don’t think they can be separated. My personal story is already political, whether I like it or not. To be born Algerian and grow up in France is to carry history inside your skin, a colonial archive that you didn’t choose but that shapes you anyway.

When I paint, I’m not documenting events. I’m reactivating what history leaves behind, gestures, faces, fragments that resist silence. The political often appears when the personal refuses to disappear. For me, art is where history exhales again, where ghosts return not to haunt but to be acknowledged.

What does it mean for your work to exist “between the sacred and the urban”?

There are days I feel torn between two worlds that barely tolerate each other, one rooted in prayer, the other in noise. I walk between them, with a mix of fatigue and wonder, trying to understand what people leave behind in their pursuit of meaning. The sacred, to me, isn’t about religion. It’s about connection, those invisible threads tying us to something larger, something that humbles us. The urban is its counterpoint: fragmented, restless, full of survival energy. My work tries to let them talk to each other. Sometimes it’s like building altars out of dust, a reminder that even in chaos, transcendence can still find a corner to exist.

Your work often brings together militants, thinkers, musicians, and anonymous figures who’ve been left out of official history. How do you choose whose stories to include, and what connects them in your visual world?

I’m drawn to people who carried light into the dark, who fought, sang, or simply existed in defiance of erasure. Sometimes it’s a thinker like (French philosopher Frantz) Fanon. Sometimes it’s a photograph of a factory worker, a mother, or a young “harraga” who crossed the Mediterranean sea without papers or promises. They all share a certain language, not of words, but of dignity and endurance. My role is mostly to listen, to connect these scattered fragments into constellations of resistance. Honestly, I don’t always choose them. They tend to appear on their own, like voices surfacing from history, asking to be seen again.

Your long-term project Borders gathers voices of the displaced and forgotten. What first inspired it, and how does it aim to “desediment” or unearth the layers of colonial and cultural history?

Borders started with a simple, almost naive question: what’s left once the map fades? I wanted to hear from people who live outside the lines, refugees, descendants of migrants, those whose memories have been rewritten or erased by power. To “desediment,” for me, means to brush off that quiet dust of forgetting, to uncover what’s been buried too long. It’s an excavation, yes, but not of land, of consciousness. Each story, each image becomes part of a shared memory that insists on staying alive.

How do collaborations, like your projects with cultural iconics including Ronaldinho Gaúcho or GACKT, fit into your larger vision?

I see them as bridges, or maybe mirrors. These figures are modern myths, complex bodies carrying the collective dreams and contradictions of their time. Working with them lets me explore how we build our idols and what that says about us. There’s always light, but there’s always shadow too.

Bourdieu once said that symbolic power only exists because people agree to believe in it. These artists embody that power, and also how fragile it is. Philippe Muray spoke about a “festive civilization” where everything, even pain, becomes entertainment. My work tries to resist that flattening, to bring a sense of mystery or quiet back into visibility.

It’s not really about fame; it’s about energy, the dialogue between art, culture, and the myths we invent to survive the world.

You live between Paris, New York, and Tokyo. How does moving across these cities shape your creative rhythm and the way you think about belonging?

Each city mirrors a different part of who I am. Paris is where I learned to fight. New York is where I started to paint. This city taught me rhythm, ambition, and reinvention. In Tokyo I found silence, precision, and humility. Together they form what I think of as a spiritual geography. I don’t search for belonging in one place anymore. I find it in movement, in translation. Home is the studio, the airport, the in-between. Maybe that’s what it means to be an artist of exile today, to turn displacement into a way of seeing.

And finally, what is your FAULT?

To have believed that one could heal the world’s wounds with images. For a long time, I thought art could repair, could stitch things back together. But sometimes, trying to fix too quickly is another form of erasure. The mistake is to forget that the wound is part of us, that it’s also a form of memory.