Bob Landström: From the Core – Making Art from Volcanic Rock

Bob Landström

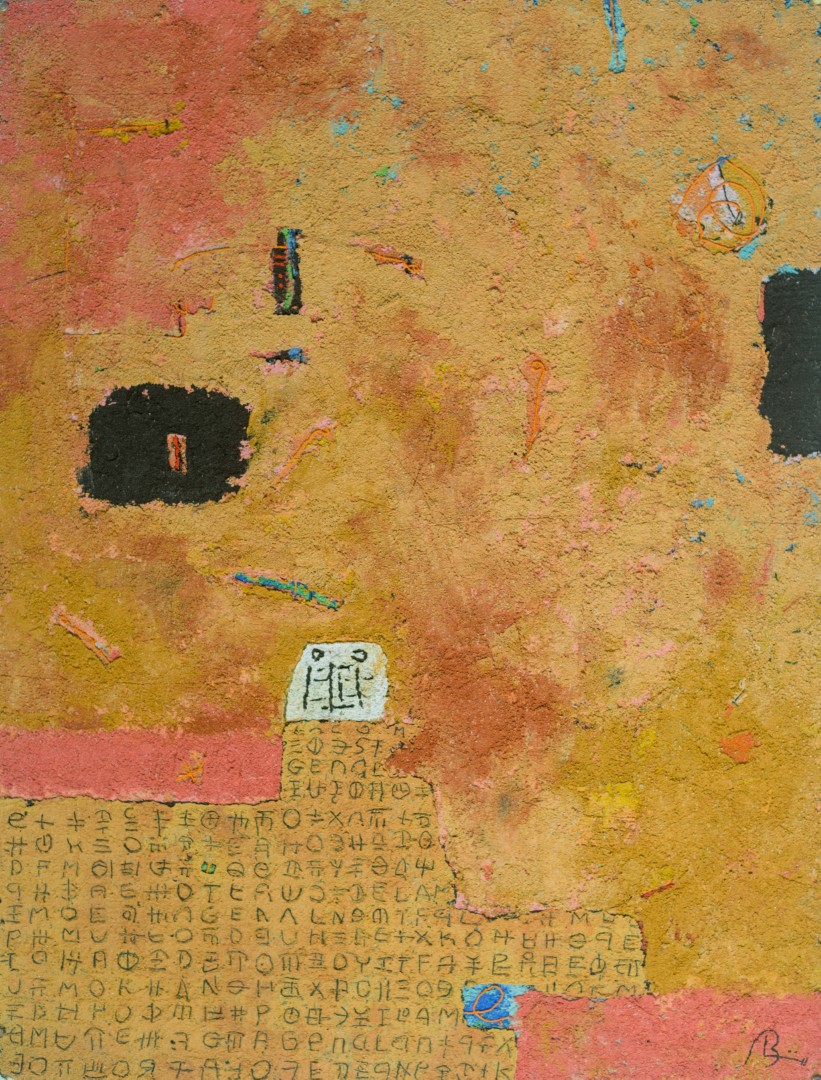

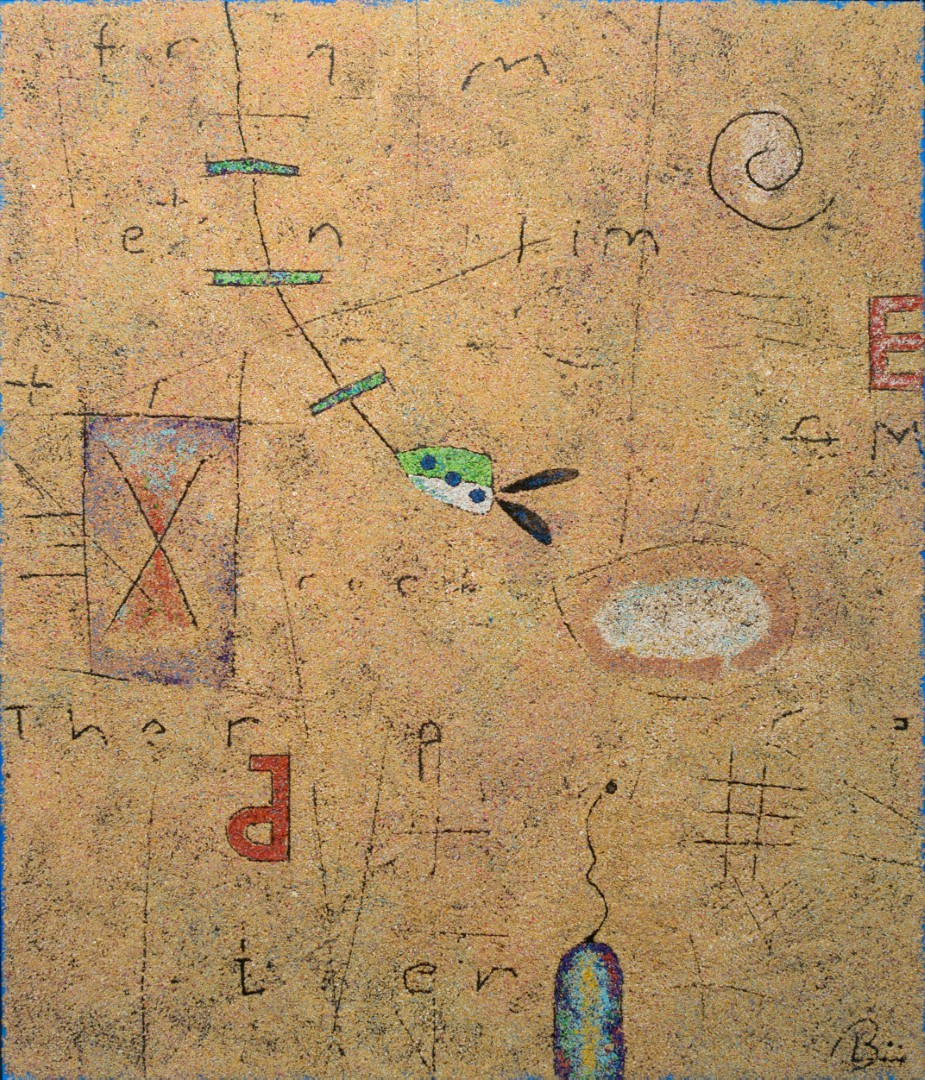

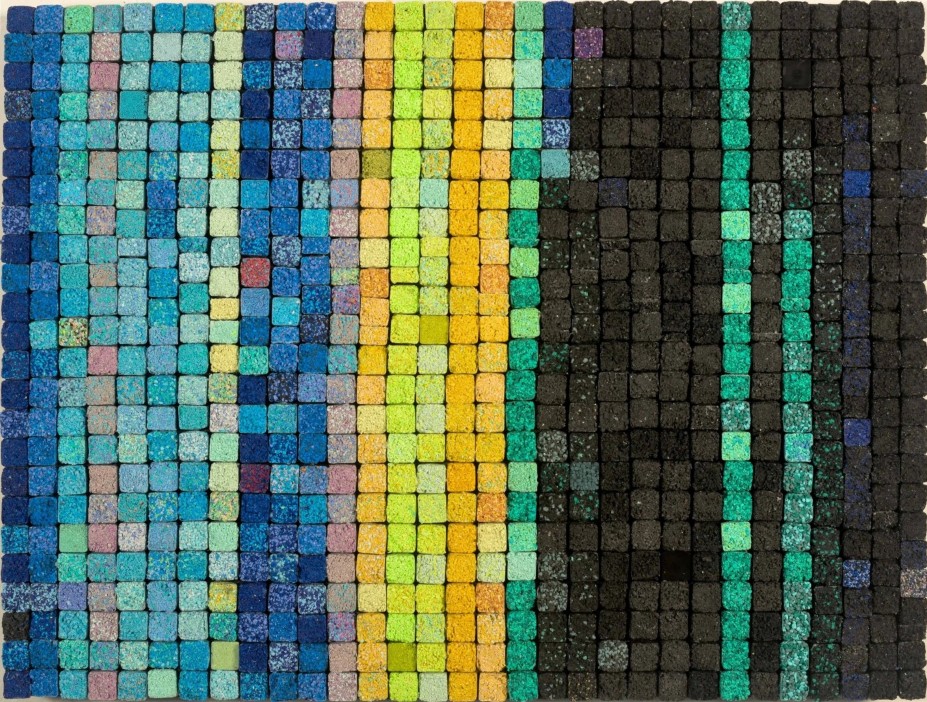

Bob Landström is an Atlanta-based artist working where science meets spirituality. He’s best known for paintings made entirely with crushed, pigmented volcanic rock—worked with trowels, knives, nails, and custom tools to build gritty, luminous surfaces.

Trained in both fine art and electrical engineering, Bob Landström explores the “pre-manifest” states of reality through symbols, field-recorded electromagnetism, and kinetic works that use sound and light to activate fragments of stone. His practice asks big questions about matter, meaning, and what connects us.

FAULT: What first drew you to volcanic rock as your main medium?

Bob Landström: Honestly, it began almost by accident. I’d been searching for a way to paint that felt more connected to what I was trying to say. At the time, I was studying Native American petroglyphs in the American Southwest, and the presence of the Earth there was overwhelming—raw, resonant, impossible to ignore. That’s when it struck me: why not paint with Earth itself? Volcanic rock carried that idea even further. It’s not just matter pulled from the ground; it’s a material that’s lived through a transmutation, from liquid fire to solid stone. That alchemical shift fascinated me then, and it still does. Decades later, I still find this material meaningful in the work that I do.

How does your background in engineering influence the way you make art?

I’ve always felt you can find ways to be creative in any walk of life. As a kid, I was just as absorbed by radio electronics and astronomy as I was by drawing and painting. Studying engineering broadened my toolkit: math, programming, circuits, mechanics. Those things don’t intimidate me—if anything, they feel like a natural extension of how I think. In the studio, that background lets me build what I imagine, whether it’s a kinetic sculpture, custom radio electronics, or sound experiments. I never set out to become an engineer, but in hindsight, it gave me the language and tools my practice relies on today.

Can you walk us through a typical day in your studio?

My day starts with coffee, then a reset: meditation, a page in my journal, or a moment in the garden. Those rituals help me focus—unless I get pulled into the digital noise too soon, and the day veers off track.

In the studio, I work on multiple projects simultaneously. I’d love to say I dedicate myself to one thing at a time, but the reality is constant overlap: painting, electronics, sound, video. Hours collapse quickly, and I often forget about lunch until late afternoon. Evenings might be dinner with my wife or meeting a friend, then usually more time in the studio before winding down. Some ideas refuse to wait; I’ll get up in the middle of the night to make notes before they evaporate.

The practice isn’t only about making—it’s also about managing. Emails, documentation, social media, finances, supplies: the unseen background architecture that supports the art. My wife keeps the inventory system alive, tracking every piece and its whereabouts. The business side of a studio practice can be very chaotic, but it is essential.

Do you have a favorite tool you’ve invented for your work?

Necessity really is the mother of invention. Painting with volcanic rock is nothing like painting with paint—it’s closer to working with sticky gravel, so brushes are useless. Over the years I’ve collected all kinds of trowels, but often I need to invent something new to get the effect I want. I’ve made what I call “rakes,” improvised from bits of wood or thin metal, each with attachments for scraping or cutting. Other tools are more like appropriations than inventions: plastic syringes for the finest grains, a clay gun for larger ones, a collection of chisels for carving precise channels into the surface. Each of these tools has evolved out of trial, error, and the peculiar demands of the material itself.

Your work often uses ancient symbols and scientific notation—what do these add to your paintings?

Symbols carry energy. A single character changes the motion within the composition depending on how it’s placed. A “3,” for example, might read as an E, an epsilon, a W, an M, or simply a cluster of lines if turned on its side. Each variation shifts the push and pull of energy in the composition in a different way. That’s the core of how I use symbols: as a way to activate space.

When characters start clustering into phrases or equations, something different happens. Fragments of language or formulae emerge, then dissolve. As I’m painting the piece, they appear, get erased, and return in another form. Sometimes there’s a hint of a message, but it’s momentary and elusive.

Viewers often approach my paintings as if there’s something to decode, a hidden message to uncover. But the truth is, there isn’t. What matters is the energy of the marks themselves, the way they charge the space around them.

How did you start recording electromagnetic fields and bringing sound into your art?

With old analog TVs, moving between channels wasn’t a clean jump—you had to dial through snow, ghost images, and bits of stray signal. I always found those liminal moments more captivating than the programs themselves. It was like peering into a secret world behind a world.

Later I stumbled onto number stations, shortwave broadcasts where anonymous voices recite precise strings of numbers. They were tools of Cold War espionage, though many are still transmitting. I started tracking and listening to them. But like watching snow on an analog TV, the static between transmissions is fascinating. You can get lost and float through the noise.

That in-between noise sparks my imagination. It has life and so much to work with. It’s literal and metaphoric at the same time. My fascination with electromagnetic static runs through every part of my practice, whether in sound, video, sculpture, or painting.

What do sound and light reveal that the paintings alone cannot?

It’s really about deepening the experience. Paintings already modulate light, but when you bring sound, motion, and light directly into the experience, the encounter shifts from something purely visual into something transportive. Sound becomes a kind of magic carpet ride for the imagination; light shapes the atmosphere around you. Together they create a sense of immersion that a two-dimensional surface alone can’t provide. It’s about giving the viewer more entry points: sight, sound, and sensation woven into a personal encounter, so the work becomes less about looking at an object and more about entering an experience.

You’ll be showing new work in GRIT with Alday Hunken Gallery this fall—what can visitors expect?

We had a photoshoot last month, and I met a number of the other GRIT artists. What struck me was the range, so many different voices and approaches under one roof. The exhibition promises to be raw and unfiltered, which feels right for the moment.

I’m bringing a selection of earlier paintings, works from 2012 through 2019. Each has its own character: one is very earthy and grounded, another has a playful energy, and one feels almost like an artifact, something unearthed from a sacred cave. Together they carry the material grit I’ve always been drawn to, but through different moods and registers.

GRIT is about persistence and the unseen labor behind making art. How does that theme resonate with your own process?

GRIT resonates with any artist, in any medium. Most people don’t realize how much unseen labor goes into a single painting or song—years of work, often a lifetime, most of it done in solitude. You show up every day, not knowing what will happen. Sometimes the work feels touched, sometimes it falls flat, sometimes nothing comes at all. But you keep going. That commitment—whether born of love, obsession, or something like divinity—is what sustains the practice. What the public sees is only the surface; the persistence behind it remains invisible.

What project or idea are you most excited to explore next?

I could answer that question differently every day of the week—there are always multiple projects in motion. Some I touch daily, others sit waiting for the right moment. Right now, I’m especially energized by my sound and video work. It’s pushing me into unfamiliar territory, teaching me new ways to think about space, rhythm, and perception. That sense of discovery keeps me coming back, and it’s what excites me most about where the practice is heading.

What is your FAULT?

Fault as in flaw, or fault as in consequence? For me, it’s more like a fault line. Pressure builds, something shifts, and new work breaks through the surface. Every painting or sound piece leaves an aftershock that sets the next one in motion. The compulsion to follow those tremors is my FAULT, and it keeps the ground moving beneath me.

If we want to talk about flaws, though, we’re going to need more time…