Tigran Hamasyan: interview with a generationally talented pianist

Tigran Hamasyan

Tigran Hamasyan is a virtuoso pianist and generational talent in the world of contemporary jazz fusion. For the uninitiated, there’s simply no context in which to place Tigran’s work: his oeuvre is dizzyingly diverse, spanning the range between jazz, folk, classical, prog rock – and, with the recent release of ‘The Kingdom’, techno – as deftly and effortlessly as any budding musician might play a simple scale. Tigran’s discography is only unified to some extent by his commitment to perpetual reinvention – taking timeless themes, concepts, melodies or structures and redefining them from an avant-garde perspective, with a sensitivity and depth that encompasses the old alongside the new.

We spoke to Tigran Hamasyan to mark the debut of his forthcoming album, The Bird of a Thousand Voices, as an immersive theatrical production at this year’s Holland Festival. Interviewing someone who the legendary Herbie Hancock described as his ‘teacher’, and whose talent has been described as ‘almost intimidating’ is precisely that, but getting a guided tour through the process of such a visionary creator is also an enormous privilege.

We hope you enjoy the journey as much as we have…

On his career so far…

FAULT: A lot of musicians have a snappy, easy-to-digest ‘artist profile’ for us journos to reel off and dip into to provide context for our questions. Your bio is more of a memoir: from your birth to date. That suggests to me that you find it difficult to box off your identity as a musician as something separate from your personal history – because they’re one and the same. Is that fair to say? And, if so, has there ever been a time in your life when you felt disenchanted with music, or drawn away from it for whatever reason?

Tigran Hamasyan: It’s true that I started my career very early [ed.: Tigran started experimenting with the piano aged 3 and was wining international awards by 15]. As I age and my career goes on, I’ve begun to experience more challenges in terms of what I represent as an artist at the “current moment” – that is, whenever I release a new project. But I see that as a very good, natural process.

From my experience, every time I face that self-reflection or realisation that “I don’t want to do this or that; I’m repeating myself”, or “that’s already been done by so many other artists in the past” – that’s a good place to be because something new is about to begin. I don’t let myself take the “easy way”.

As the quote from The Bird of a Thousand Voices (paraphrased in many other ancient tales) says, “at the crossroad of the three paths, you have to choose the narrow and rugged path, because that’s where one can find the enchanting bird that will bring resurrection from the ashes”. This universal endless cycle of sleep->hard path-> awakening or death and resurrection is a reality that we should embrace and not be afraid of. Nothing meaningful and good comes from taking the easy, comfortable path. The easy way is a trap: taking it means you don’t grow yourself and you don’t help others to grow either…

On his radical change of musical direction with The Bird of a Thousand Voices…

‘The Kingdom’, your debut single from this album, represents a significant departure from your previous releases – even considering the eclectic nature of your back catalogue, which touches on genres ranging from jazz to folk to ‘contemporary classical’. What prompted such a dramatic change of tack?

This music was directly inspired and composed for the Armenian ancient tale named The Bird of a Thousand Voices (Hazaran Blbul in Armenian). After I stumbled upon this tale, my life hasn’t been the same. It’s a really powerful story, and it’s given me an enormous impulse to create. As it was my first time making an album on a “libretto” – and such a culturally significant one, at that – I decided that the music had to embody what, for me, is the life-changing capacity of the tale itself. In practice that meant I wanted to erase everything I had done before and write something totally new for it.

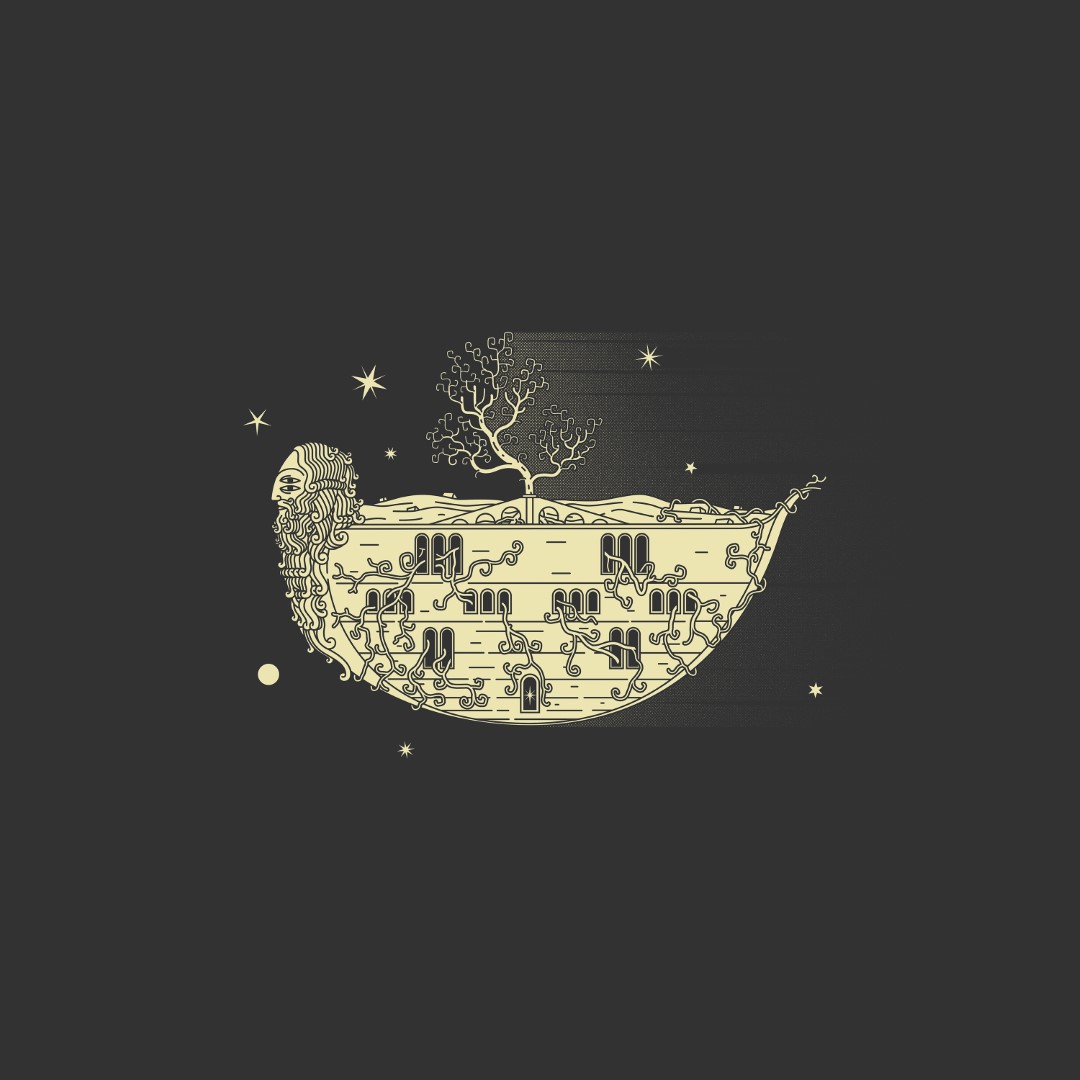

The melodic content of ‘The Kingdom’ is my way of trying to encapsulate the feeling and possibly even elements of the sound popular in the times of Sumer, Hittite, Urartu or medieval Armenia… Beyond that, I wanted to channel melodies for a mythical King’s court that lived in idealised times marked by “divine” harmony and prosperity.

I’m fascinated by that concept: the music that may have existed in semi-mythical ancient kingdoms. There is no definitive evidence of what pre-Christian and/or very early medieval melodies sounded like. As an artist, I allow myself to muse or day-dream on the subject but I do so through the ears and eyes of a time traveller from the 21st century who has found a portal to that world. As such, the harmonic, rhythmic and sound quality of my compositions is expressed through that lens. Overall, that’s why the orchestration of ‘The Kingdom’ (and the rest of my upcoming album, for that matter) is very synthesiser-heavy: it’s 21st century fantasy to symbolise the feeling of medieval myth.

Most importantly, I wanted the composition to make the listener think about this enchanting and divine mythical bird that lives in a realm outside of our material world. The track is a gateway; the start of a story: a journey to find this incredible, magical bird.

‘The Kingdom’ is the first single from your forthcoming album, The Bird of a Thousand Voices (expected August ’24). The album has Armenian folklore at its heart, and specifically the tale of Hazaran Blbul. Can you elaborate a bit on what about that story inspired you? And why now, in particular?

Although it’s technically just the ‘prelude’ to the musical telling of folk-tale The Bird of a Thousand Voices, ‘The Kingdom’ actually contains the entire story within it. It tells you about the kingdom where a kind hearted king lived with his three sons. His kingdom contained a beautiful garden in which one could find all the fruits of the world. An old woman’s curse marks the beginning of this epic story: the king’s garden withers and dies, and his subjects turn into heartless beasts. The only thing that can save the king’s garden and his people is the song of the mystical bird of a thousand voices. But to find this divine bird, one needs to take the dangerous “path of no return”, facing demons and numerous temptations along the way.

The main melody, with its fast-cascading “cosmic rays” of arpeggios, represent the bird and its otherworldly, timeless and divine quality. It also sets the mood for our hero the prince’s journey and his determination and sacrifice to bring back the bird to his father’s kingdom.

On his twin sense of belonging and responsibility to his native Armenia…

Formerly a member of Armenia’s huge and widespread diaspora, you moved from LA back to your home country in 2016. Given the opportunities intrinsic to living in (arguably) one of the Western world’s cultural Meccas, why did you decide to take that step?

I find that it doesn’t matter where you where born or which ethnicity you are: you automatically inherit the responsibility to take care of and contribute to the place you grew up and the people who nurtured you. Every country has its challenges but your place of birth is something you can’t control. Over time, you realise that there are things about your homeland that go beyond your “liking and comfort”. At that point, it becomes more about how you see your role in the community. You have to have the mindset and courage to take responsibility and do what you can for others as well as for yourself!

I feel at home in Armenia and I want my kids to grow up speaking, reading and writing in Armenian and carrying this culture. I find inspirations and challenges here that I didn’t – and don’t – find in LA or New York. I guess that, in itself, gives me a responsibility as an Armenian to be here and to contribute to the community in Yerevan and the country as a whole.

You remain popular in Turkey despite your outspoken comments on the Armenian genocide, including your public refusal not to play in the heartlands of Turkey following the release of Luys i Luso in 2015. Does that surprise you?

No comment.

As a founding supporter of Berklee’s Armenian Scholarship Fund, your role of selecting Armenian musicians to participate in a Berklee-run development program provides a bridge for talented individuals and, generally speaking, Armenian culture to access the US and the wider English-speaking world. Given Armenia’s historic and contemporary ties with Russia, how important do you think it is to provide that ‘cultural counterbalance’?

I hope that Berklee’s Armenian Scholarship Fund will one day see its financial goal accomplished. These days, it seems that much greater importance is given to science and technology, and music and the arts in general are seemingly secondary to them. But it’s a fact that people remember eras by specific artists who have created inspirational and culturally significant pieces of work. It’s great art and great music that inspires generations, arguably more so than breakthroughs in STEM.

Berklee is somewhere jazz music thrives and, generally, education thrives, so it was a natural choice for me to collaborate with them.

Why do you think that ethnic Armenians from such different spheres of influence – from yourself to the Kardashians, the late Kirk Kerkorian, and so many others – are moved to speak out on the genocide, engage profoundly with the Armenian community, or otherwise give back to their country of origin however they can?

No comment.

On collaborations, and more…

The Bird of a Thousand Voices is set to be a multimedia offering: ‘The Kingdom’ was released with a corresponding online game and the album will debut as an immersive theatrical production at this year’s Holland Festival. What’s the intention behind that: is it primarily a tactic to reach a new audience?

That’s a bit reductive: the intention is to tell this important story in a new way that will have an impact on the human being living in 2024 – especially the younger generation. Thousands of years ago, a master storyteller would tell this story on certain days in a village around a fire or in the barn next to a fireplace. He or she would take people on a grand journey from dust til dawn – often-times accompanied by music as well. These are the environments where things have developed into “theatre“ and “opera”. Myself and Ruben Van Leer, who is the co-artistic director of the trans-media experience, have devised a means to tell this story in such a way for our modern day audience to experience it in a way that stays with them. It’s entirely different to listening to music on its own: it’s more of an immersive experience designed for participants to feel the grandeur of the tale through various artistic means.

I have worked with Ruben on a few occasions previously. He has made two music videos with me, we worked together on one live solo performance, and he created live visuals for my album release concert in Paris in 2013 at the Cité de la Musique. It has been really inspiring to work and to spend time talking about with Ruben about our work and the idea of pushing the boundaries with new projects…

His film Symmetry was a huge inspiration to me and when, I started working on The Bird of a Thousand Voices, I thought that the project needed a real visual side to it. I mentioned it to Ruben and we started talking about it over a couple of years: firstly about him creating the live visuals, and then things developed into making a film.

This ancient tale comes from such a deep place that one connects to it no matter one’s heritage. These ancient myths and tales are part of our collective unconsciousness and, in a way I wanted a non-Armenian person to make a film about this story to illustrate our multi-cultural connectedness that goes back to very ancient times.

Who would you most like to collaborate with and why?

Jan Garbarek. He is a great inspiration and the trigger that made me discover folk music and my own cultural heritage. I have this feeling of timelessness and eternity connected to a lot of his albums/compositions and it’s my dream to do an album with him….

If you weren’t making music, what would you be doing?

I can’t say I’ve ever loved anything else as much as music to really evaluate this question! Film director comes to mind first. Beyond that, maybe archaeology…?

What is your FAULT?

Self-centeredness, materialism, lying to myself, negativity, wasting time and other demons…