FAULT Focus: Khadija Saye: Remembering The Artist Through Her Photography

Early Thursday morning, the reality of London’s Grenfell Tower blaze hit home for myself and my fellow UCA alumni as we read the final Facebook update from our once classmate, Khadija Saye. Trapped within the burning building, Khadija reached out for prayers from her loved ones, and they rushed to the streets and social media in hopes of finding her. Sadly, the next day Khadija’s family would confirm that what we feared the most had come to fruition, Khadija had tragically perished in the blaze.

While we did share a class throughout university, myself and Khadija were not close friends. Remembering my panic as I scrolled Google and social media desperately looking for an update on her condition, I feel compelled to help ensure that her captivating body of work and not the tragedy of her passing, form her lasting legacy.

As an artist, her work cast a light on Gambian culture, the collective unity within “the other” and her journey into self. In memorial of Khadija and the conclusion of her photographic portfolio, FAULT takes a dive into the work of the late great artist – Khadija Saye.

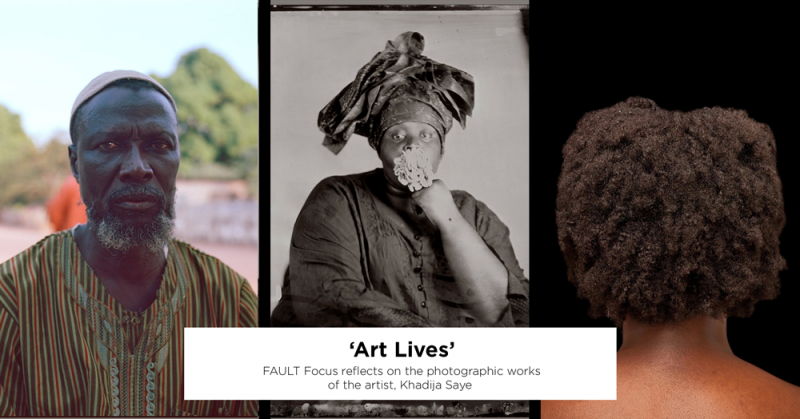

In 2013, Khadija took her seat at the proverbial table and unveiled her centrepiece in the form of her photographic project entitled, ‘Crowned’. This series of photographs is one of the projects that our class was able to observe as it developed from inception to completion as Khadija’s final degree show series. ‘Crowned’ is made up of eight portraits showcasing the different ways in which black woman close to Khadija styled their hair. From woven braids, extensions, dreaded and natural afro, the viewer is given a glimpse into the diverse range of hair styling possibilities open to black women.

Entitled ‘Crowned’, Saye references the physical and the symbolic idea that black hair is something to be prized and adorned and not ashamed of. The words of Ingrid Banks taken from her book entitled ‘Hair Matters: Beauty, Power, and Black Women’s Consciousness’ echoes in my mind when I reflect upon Khadija’s title choice. In the book, Banks writes:

“Crown suggests a source of power, excellence or beauty…Therefore, a notion of power is embedded in the idea of hair as a black woman’s crowning glory. Hair has the ability to become a foundation for understanding how black woman view power and its relationship to self-esteem” – Ingrid Banks 2000.

More contemporary references to black hair as something of brilliance can also be seen in Solange Knowles’ critically acclaimed 2016 release ‘Don’t Touch My Hair’, where within the opening verse Solange exclaims:

“Don’t touch my crown, They say the vision I’ve found”

“They don’t understand, What it means to me”.

One does wonder what significance Khadija’s perception of her own afro hair and its beauty played in her choosing to embark on the project and if I were to guess, producing ‘Crowned’ was a labour of love and presentation of self-pride. Indeed in March 2017, four years after the release of the series, Khadija reminisced on the making of the project in joy tweeting:

This time 4 years ago, I was in the process of shooting my Crowned series with £0, just some black velvet with beautiful friends & family pic.twitter.com/Ykz6seBKjE

— Khadija Saye (@Saye_Photo) March 5, 2017

In the image, her young assistants observe possibly unaware of the importance their participation played in the construction of ‘Crowned’ or how it might affect their perceptions towards their afro hair and ideas of self in years to come; truly the impact of ‘Crowned’ will stretch on far further than even Khadija would have imagined.

As the only black male on our course, I once attempted to play up my “wokeness” and asked Khadija if she had seen “the Chris Brown documentary called ‘Good Hair’”, (misquoting Chris Rock’s 2009 documentary that focussed on the perception of natural hair within the African-American community.) Emblematic of her kind-hearted and gentle attitude, Khadija, of course, corrected my mistake letting out a light giggle; dropping my façade I listened to her thoughts on the documentary.

Earlier I referenced Solange Knowles’ ‘Don’t Touch My Hair’, a fiery anthem that highlights the resentment caused by patronising actions which decrease afro hair to a thing of play but observing ‘Crowned’, the same frustrated narrative does not confront me. My interpretation of ‘Crowned’ isn’t, “don’t touch my hair!” It is an inviting, “Don’t touch but do see. Bear witness to the beautiful ways black women can choose to style their crowns.” The viewer is invited to marvel at the intricacies of the different twists, curls and over-locking structures of the sitter’s hair and when printed and framed in a gallery, we’re disarmed and hypnotised by their sophisticated beauty.

It’s important we recognise the personal connection Saye shared with the women she photographed. The trust the sitters have placed in Khadija is unique; formed not just from a shared experience of blackness but through the confidence these women placed in Khadija’s skill as an artist to capture so much more than just hair. It is thanks to her affable character that Khadija was trusted to capture up-close the art within her subject and through her artistry and presentation nous, she allowed the viewer to appreciate black women’s hairstyles up close as something of splendour.

Khadija’s ‘Crowned’ might end here, but the project as a form of inspiration to a new generation of artists will continue. The eight sitters included on Saye’s website are but a drop in the ocean of the many different ways black woman can choose to style their hair; making ‘Crowned’ a gleaming seed from which the mightiest body of work can still grow.

For her series entitled ‘Home.Coming’, Khadija travelled to The Gambia and documented her exploration of self through a series of portrait and landscape photographs.

Something I notice through all of Khadija’s work is her ability to find familiarity and gain trust within cultures sometimes seen as ‘the other’. ‘Home.Coming‘, ‘Crowned‘, ‘Eid‘, ‘Madame Jojo’s‘, all focus on different categories of the human experience yet notice how she has never been kept at arm’s length from her subject. I don’t feel the presence of a white tape that Saye is forced to photograph from behind when I observe her work. When capturing her subjects, for a time at least, Khadija is one with their environment and through her lens’ eye, the viewer is too.

For me, the unseen friendship-building and conversations Saye would have had with each person to earn their trust before the photo session conjures much intrigue. The above portraits arrest your gaze; the men’s eyes tell countless yet frustratingly unattainable stories. Khadija has stopped time but for a moment yet opened the door for myriads of questions – made sorrowfully more perplexing now they’ll go unanswered.

In another photograph from the series, a young girl smiles as she watches something out of the frame and in the below photograph a man leans on his prized Volkswagen, both beg a mountain of questions yet if we take a step back, we’ll find Khadija’s story told throughout the series.

Any second generation migrant knows all too well the conflicted notion of “home”, and from what I can only guess, Khadija travelled to The Gambia to find, explore and reflect on life in a home in which she did not live. While the content of Khadija’s photographs doesn’t answer the question of “did Khadija find self and the comfort of home while in The Gambia” but we need only look at her sitters to find our answer. As referenced previously, her subjects are unperturbed in front of the camera and this is likely because they were relaxed with their photographer. Any artist can tell you the anguish of requesting a portrait of a stranger only to watch their sudden discomfort when faced with the intrusive camera lenses flung in their face but notice the air of calm in Khadija’s work.

Yes, each photograph in the series contains countless untold stories, yet one is clear, and it’s the sitter’s tale of Khadija. As a photographer, she wasn’t a stranger in their midst nor a second generation displaced entity forcibly taking up shop in their domain; for that time if only for a moment, Khadija Saye was one with them – truly at home.

Dwelling: In This Space We Breathe

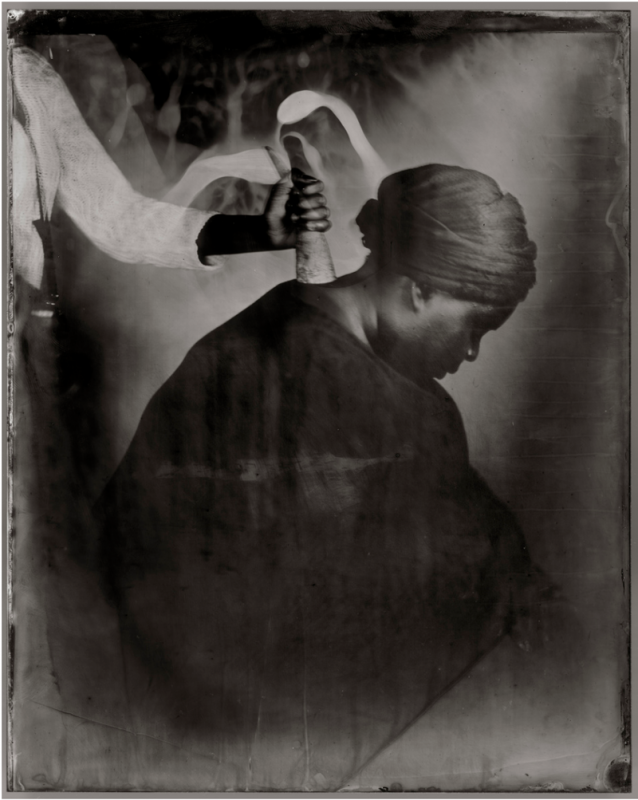

Khadija’s last exhibited work ‘Dwelling: In This Space We Breathe’ made with the help of artist, Almudena Romero, saw her once more exploring her heritage by investigating traditional Gambian spiritual practices and the comfort practitioners found in the arms of a higher power.

There is something remarkably poignant about her final project immortalised on such a physically existent format such as the tintype. By using tintypes, Khadija transformed her amorphous visual being, memory and legacy from a temporary state and gave it physical form. Unlike a digital file, memory or spoken recollection, her tintype image has weight, texture, smell and uniqueness the very same way our physical forms do; yet unlike us, her tintypes do not have an expiration date and will always remain.

The very idea of legacy and the pursuit of artists to leave a token in this world for after we pass, itself is a practice of spirituality. For all we know, there is no telling of what significance our life actions will play after our lives come to an end, yet we attempt to leave proofs of our existence to tell the future world “I was here and I existed.”

In the tintype images, Khadija is depicted in a ritual using sacred Gambian artefacts meant for the purpose of connecting with the spiritual world from the physical plane. Now with her passing, there is a spiritual awakening of ideas and ways of reflecting within the viewer. Now as we gaze upon the imagery, it is us the viewer who are being connected with Khadija and in turn, linked spiritually to the “once was”.It is through Khadija’s immortalisation of Gambian ritual that we now look upon her from this physical plane despite what would be considered by many religions as her soul ascending to a higher state of being.

I’ll admit that the above sounds somewhat of a stretch and likely not what the project was intended to symbolise, but it did cast a light on my scepticism towards schools of beliefs that I do not understand. In reflecting on the work, my own westernised perception of spiritual ritual has come into question. For myself at least, the actions depicted by Khadija provides a brand new outlook and way of seeing such ceremony.

For some of those raised in the UK, the idea of spirituality and non-conventional western religion is sometimes considered as something of myth or fantasy, not necessarily through conscious choice but through our conditioned view of pre-evangelised spirituality.

In Sir Edward Burnett Tylor’s 1887 book (now somewhat offensively entitled) ‘Primitive Culture’, he gave the broad belief that spirituality can be attributed to ritual and inanimate objects the name ‘Animisim’.

Note: ‘Animisim’ does not exclusively describe the Gambian ritual Khadija explored in her project but broadly refers to the school of similar beliefs held by people throughout Africa, Europe, Asia and Australia throughout history. Hopefully an anthropologist or practitioner of the specific belief Khadija explored can provide a more suitable title for us to use in this essay.

While coining the English term for the phrase, Tylor knew he was generalising a large number of people, but he did so out of frustration with writers of his day who saw such displays and dismissed them as illegitimate forms of spirituality.

“Short of the organised and established theology of the higher races as being a religion at all. They attribute irreligion to tribes whose doctrines are unlike theirs”. – Taylor 1887

The link between the photographic process and spirituality is also drawn upon in the accompanying text for ‘Diaspora Pavilion 2017’ where the works are currently held on display.

“The process of submerging the collodion covered plate into a tank of silver nitrate ignites memories of baptisms.” – Disapora Pavilion 2017

It is clear Khadija found a spiritual link at every step of this project even choosing herself as the subject when producing the tintypes but rather than theorising or projecting, it’s only right to let the words that accompany the project have the final word:

“This work is based on the search for what gives meaning to our lives and what we hold onto in times of despair and life changing challenges. We exist in the marriage of physical and spiritual remembrance. It is in these spaces that we identify with our physical and imagined bodies. Using herself as the subject, Saye felt it was necessary to physically explore how trauma is embodied in the black experience.” – Disapora Pavilion 2017

Notice how throughout Khadija’s entire body of work, there’s a level of thinking that transcends just the art of seeing. All three projects spoken about above are unique individual displays of artistry and wonderous displays of photography worth that of an artist far beyond Khadija’s years.

‘Crowned’, ‘Home.Coming’ and ‘Dwelling: In This Space We Breathe’, are all linked only by the artist of origin and much like Khadija, they mean and will continue to mean so much to so many different people. Reminiscent of the Khadija that I knew from across the lecture theatre, not a lot is shouted nor is it displayed with over-the-top performance – because work and artists with true substance donesn’t require such theatrics.

This week we sadly lost Khadija, but not her contribution to the artistic world.

See more from Khadija’s portfolio on www.sayephotography.co.uk