FAULT are proud to host this exclusive interview with artist Andrew Salgado, whose paintings are large-scale works of portraiture that incorporate elements of abstraction and symbolic meaning.

1) TEN is the celebration of a decade of your art; how did it all begin at the very beginning?

I was always interested in painting – even as a kid. I was one of those odd, kinda girly, kinda awkward kids that would fake sick for soccer practice but was like, enrolled in pottery classes and making Tiffany lamps at 11 years old. I mean, in the end it worked out for me but I was a private kid. I had a little playroom as a child and would just spend all day drawing and painting and playing with LEGO. I think it makes sense that as an adult, I’m basically doing the same thing. Realistically, it wasn’t until I was in high school that I had a seminal two years with a teacher who pushed me to pursue my art further. Prior to that I had always considered art as a hobby… I mean, I come from a family of academics; you just didn’t go into university for painting…the thought that I might pursue a Fine Arts degree was pretty frowned upon at first. My parents’ friends would ask me what I was taking in university and then there would be this awkward conversational limbo when I had to clarify that I was taking ‘Fine Arts’ and not ‘Finance’. Its just always been the most defining characteristic about me. I’ve often said that without art, I’m nobody. I’m a non-person. Talk about co-dependency!

2) What and whom inspires you?

As a younger artist I used to think inspiration had to come from some divine fount. Like, everything had to be big, operatic, melodramatic. As I mature, inspiration comes from smaller, more intimate sources. Sometimes it’s a conversation; a song; a poem; a memory; or even silly things…I did a painting called “Oh!” Which was inspired by a kid’s paper party hat that I found in my studio.

My exhibition “The Fool Makes a Joke at Midnight” was inspired by the death of David Bowie and the resulting painting was called “Sound & Vision”. Sometimes the subject provides inspiration…my favourite subject is painter Sandro Kopp, who is also Tilda Swinton’s partner… I don’t like the word ‘muse’ because I think its overused, but he, along with model and friend Anna Cleveland, were the original sources of inspiration for my show “The Snake”. That eventually evolved into something much bigger…the show discussed homophobia, Islamophobia, xenophobia, and I even painted my first transgender subject in “Chrysalis (Portrait of a Girl)”. Little things can become bigger things, but “The Snake” took me to darker places that I was fully prepared to go.

Lately, installation has been integral to the reading of the work. The paintings are stretching their limbs beyond their own confines. I just want to let them breathe, and take me on a journey that is more irreverent. I don’t want to be so political right now. The world is ugly enough, I want to have fun and make people smile. For my next show, I’m keeping my head above the water. I’ve asked Australian artist Rhys Lee to make sculptures to accompany my paintings, and we’re doing a show called “A Room With A View of the Ocean”. My assistant is currently sourcing lemon yellow furniture…if that tells you anything. Right now I’m inspired by freedom. Possibility. The idea of an endless horizon. That gives me room to experiment.

3) How have you grown personally and creatively over these ten years, and how do the ten images selected for this exhibition, reflect that period?

Well it really is the Design of a Decade, hah, to quote Janet Jackson. But seriously, I’ve changed as an artist and as a person. I’ve grown into myself and so have the paintings grown into themselves. The show was curated by David Liss of the Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art in Toronto. After he agreed to curate the show and write a foreword for the corresponding monograph of my work, also entitled TEN (available for purchase at

www.andrewsalgado.com or my representing gallery Beers London), I presented him with about 35 works that I would be okay with representing various periods of my work for a survey exhibition. There was one piece that for some random reason the owner wouldn’t lend back to us, called

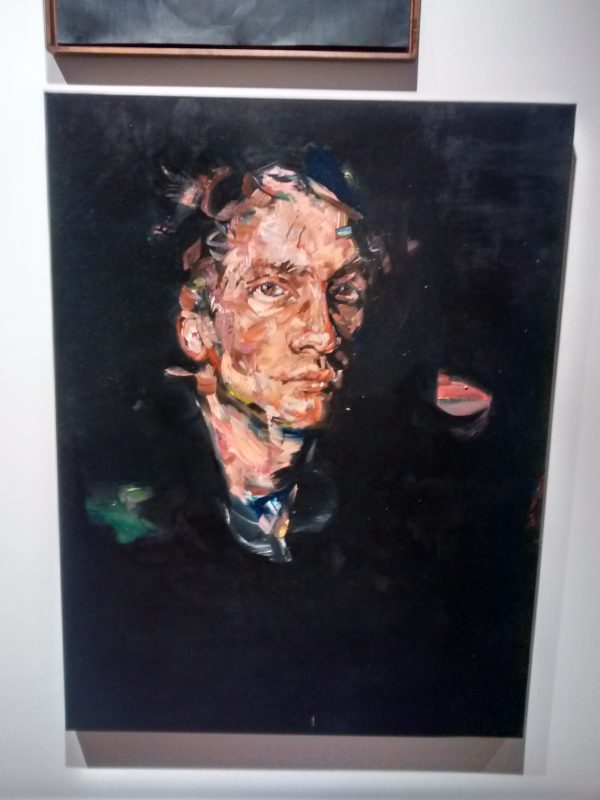

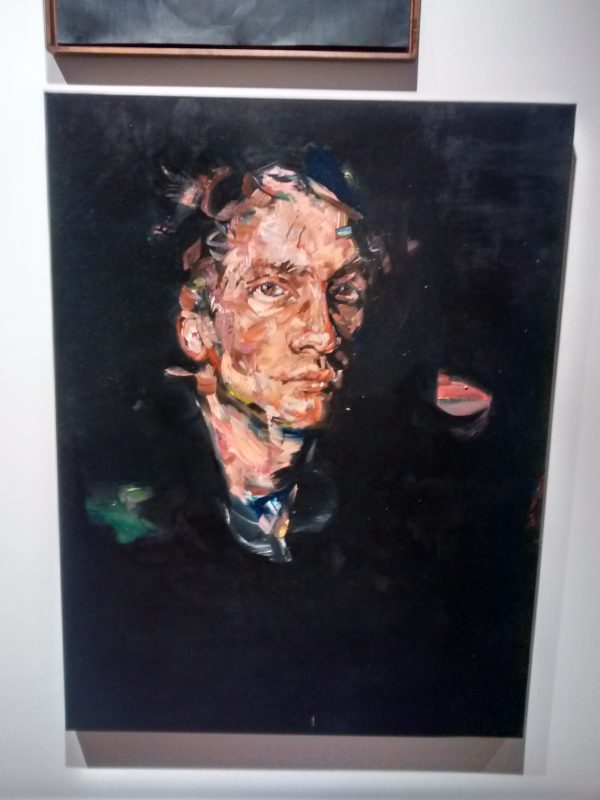

It Is The Fear that Keeps Us Awake, so I do think that there is a slight jump in the presentation wherein that period of a deconstructed face is missing…but overall, I’m focusing on the future, not lamenting the past. The first piece selected was

Schismatics, a painting of one of my closest friends from 2006. Then you see paintings that exhibit a lot of pain after I was assaulted in a hate-crime in 2008…and then, well, you see me sort of…grow out of that. Into a more confident, happier, perhaps even more spiritual place, where I am now. You see that spirituality in

Afterlife / Osiris. David and I spoke and I realize that there is a real sense of optimism in the show. I guess that reflects my outlook in life as well.

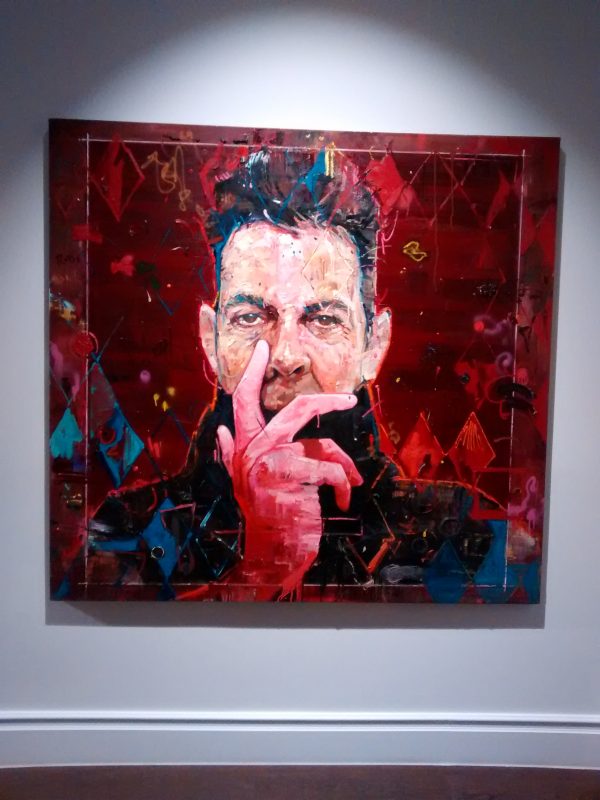

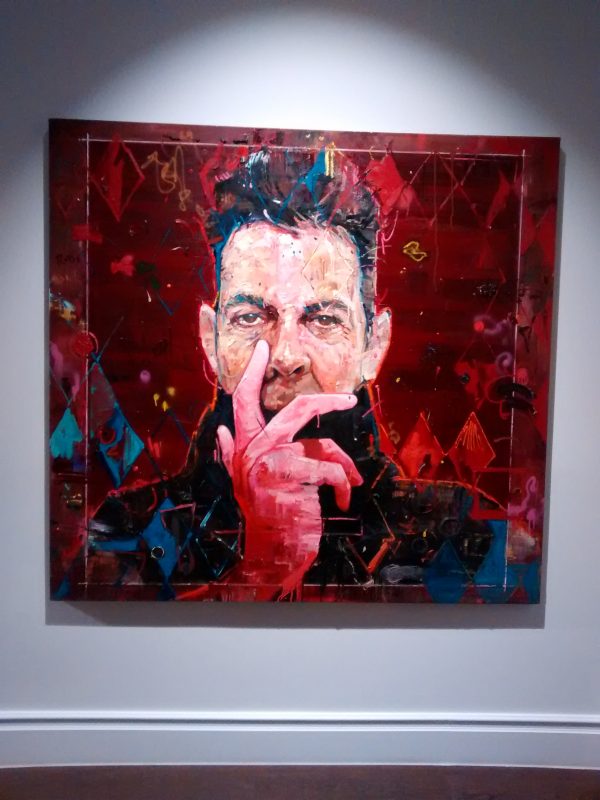

4) ‘Black Dionysus’ is a particulary striking piece. One of your earlier pieces, and much darker than more recent works. Tell us about that work?

There are a few of these Dionysus paintings. Black, Green, and Pink. I love the idea of this somewhat tortured archetype of the bacchanal. He’s the opposite of Apollo – the god of Order – he represents these wild, drunk, creative but sometimes destructive ideals. I think I see that in myself. I’m definitely more aligned with that mythos than anything other. You’ve seen it before as well with Caravaggio and countless other artists. We relate to that. The Ancient Greeks, the Classicists, the Neo-Romanticists…I mean, he appears countlessly.

I think there are some beautiful hesitations in that piece. I wasn’t as confident and it shows.

5) I first became acquainted with your work, when it was featured in the Harvey Nichols windows. I assumed that it was the colours that had originally caught my attention, but later I came to realise that it had in fact been the portraits eyes. Are the eyes “windows to the souls” of your subjects?

You know I really sort of try to avoid this idea. In my previous show

The Snake at Beers every subject had obstructed eyes. As an artist, you have two choices – the first: feed into your audience and give them exactly what

they want, which typically is at odds with what you want, creatively, as an artist. The other option is to challenge yourself and your audience, and I prefer to take that route. None of the works offer easy answers, and so in all honesty when people say ‘I love the eyes in your paintings’ it makes me want to take a scraper and scrape it right out. In fact, a lot of the eyes I do are scribbled right over. I like the idea of making beautiful things ugly, and ugly things beautiful. No, I don’t think the eyes are the windows to the soul. The painting emits a sensation and a feeling as an autonomous whole. One part is no more or less important than the next…I mean if it were just about pretty eyes I’d just sit around painting pretty eyes all day. I want to make things more complex. If you look at a painting like Orlando, for interest, I literally scribbled right over the eyes. In

Chrysalis, they are hardly both hardly painted whatsoever and then also literally stitched overtop with needle and thread.

6) Your works often portray an almost savage level of raw emotion, laying bare the layers and complexity, of each subject. How do you so successfully achieve the transference of the emotional connection, that you clearly establish with your subjects?

People bring up this notion of ’emotion’ often when talking about my work. I really don’t know. I have something important that I’m trying to say, I respect my subject, my process, my viewer, my collectors… I just believe fundamentally and fully in what I do. So with that sort of respect for the artwork, I guess something makes a connection. I don’t have a crazy high output – I think it was 24 paintings in 2016…so there is a lot of time spent considering the works and the process. They have to connect with me and the viewer and if they don’t, they will never leave the studio. I think a lot of artists cut corners, or art – or become – lazy. That doesn’t cut it…I’m always working, and trying to improve, and so far people have responded to that.

7) Love, loss, life, pain and emotion are all words that your work conjures for the viewer. I an age where many men are now coming to grips with their mental health, do you intentionally reflect this important issue in your work?

Wow I’m so happy you brought this up. Its in there, buried deeply. I suffer from overwhelming anxiety that – if not attended – means I cannot produce. So I deal with that, medically. But I think one of the first problems with mental health is that label; the second problem is how widespread

and how frequently it goes undiagnosed. People are suffering, but we arent talking about it. Somehow, through my work, people open up. We share an experience together. Often, but not always, I have strangely deep connections with my subjects through the process of painting them. Then we become friends, and its like we speak in a new language together. We have connected through a bond wherein I understand them – and they understand me – on a different level. Its weird. I sound crazy. But its true.

8) You stated that often “you didn’t have faith in yourself” how did you overcome that?

I surround myself by people who support and believe in me. Its a lonely job – this artistmanship. My job is to spend 8 hours a day self-critiquing my every single goddamned mark, movement, brushstroke, and creation, so if you’re not careful, that can take you to a dark place. And if you’re an artist who isn’t doing that, well then quit. Because you’re wasting our time as much as you’re wasting your own.

9) To all those “kids from the praries” out there with pots of paint, what advice would you impart?

Work twice as hard, worry half as much. And support your peers; we’re in this together.